We know that feedback done well makes a huge impact on employee performance. We also know that too often feedback isn’t done well or isn’t done at all.

It remains a potent tool, where the potential impact is out of all proportion to the time required for preparing and delivering any feedback.

And now, regardless of how each organisation or team is intending to structure their work, with concerns about productivity, burnout and connection at an all-time high, the importance of well-considered, timely feedback has never been greater.

Imagine creating a culture of feedback in your team where there’s sufficient trust, psychological safety and skill to ensure that everyone is not only comfortable providing feedback to everyone else but also habitually asks for feedback too.

An ongoing ‘cats cradle’ of feedback in the team, will require an amount of collective courage to start, but once up and running will help remove a lot of the fear that gets in the way of exceptional team performance.

How to create this virtuous culture of feedback?

Ask for feedback

As with most things, it pays to start at the top. And not necessarily by imploring team leaders to give more feedback.

Rather counter-intuitively, one of the best ways to kick-start a culture of feedback is for the leader to regularly ask for it.

In Radical Candor, Kim Scott calls this ‘Seeking impromptu guidance’, which is about inviting criticism from your direct reports. Receiving ‘in the moment’ critical feedback increases self-awareness and helps leaders learn and grow. It’s helpful to know when you’ve got spinach stuck in your teeth, after all…

It’s rare that teams are comfortable with such candour at the outset. Foundations need to be set and a conducive environment created.

The team leader needs to provide some context and discuss what they’re trying to do. A request for criticism out of the blue might just seem weird.

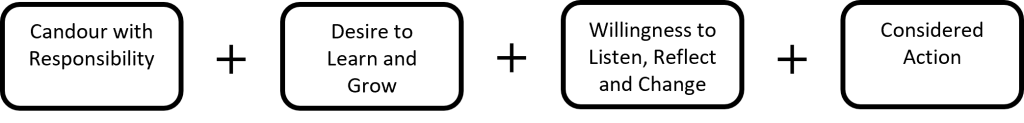

There should be some ground rules. Things like candour having to come with responsibility. Tough messages should be encouraged, but only when delivered with care. And if the team are going to be convinced that this is a good idea, they need to be sure that the leader will respond positively, that critical messages aren’t followed by defensiveness, that there will be no negative repercussions for the feedback giver and that effort is made to change in response to helpful feedback provided.

This will probably be a big shift for the team leader and team. It will require courage on both sides and persistence. It’s likely to take a while but stick with it and keep talking about it.

As it becomes more natural and team members are more comfortable providing critical feedback to the team leader, start discussing how the team could ask for feedback from each other. Why should feedback always come from the line manager anyway?

Build group feedback habits

If you want to develop feedback habits, then you have to surround your people with feedback. You’re already asking for more feedback yourself, encouraging candour and showing the required vulnerability. You’re modelling openness, discussing feedback and encouraging more of the team to request it from their colleagues.

Next, you need to establish feedback as a core team process.

One approach with multiple benefits is to institutionalise a team review process, something like an After-Action Review, where the team routinely discusses what’s gone well, what’s gone less well and what needs to be different next time. Make sure these happen for every key action. Challenge the team to be bold in their evaluations and to not shy away from being critical in pursuit of improvement. Also, to maintain the integrity of the process, make sure to follow up on all action agreed.

The rules, such as ‘Candour with responsibility’ must apply, but for these sorts of reviews to be most valuable, the team needs to be steered beyond the anodyne.

Another technique, referenced in the September 2021 Better Yet newsletter is ‘Red Teams’. This idea, borrowed from the US military, involves chartering a group, perhaps within the team, to critically evaluate important decisions, actively looking for weaknesses or oversights. The ‘Red Team’ then delivers what may be difficult feedback messages to the decision owners, crucially allowing them time to make any adjustments before they go live. Apart from normalising honest discussion, this process helps team members get used to hearing tough messages, whilst also establishing feedback as a mechanism for improvement.

In my work as a Team Performance Coach, I’ll sometimes encourage teams to add a feedback set piece to their meeting agendas, perhaps monthly or quarterly. This simple process asks everyone to bring to mind the team’s purpose and most important deliverables. Then, going round the table, focusing on one participant at a time, the rest of the team tell them about the one thing they do that contributes most to the achievement of the purpose and deliverables. This usually increases positive energy and leaves a warm glow. It’s then important to build on the momentum and move things up a notch. The same process is used, but team members are asked to tell their colleagues what one thing they could do differently to have an even bigger impact on the purpose and deliverables.

Again, it’s about making both giving and receiving feedback a normal part of being in the team.

It seems to be a no brainer. Teams that master feedback are likely to be more psychologically safe, more connected, engaged, innovative and ultimately more successful. Feedback is one of the most important levers we have. It’s not rocket science, but like all good things, it does require effort and courage from the team leader to go first, create the right conditions for feedback to thrive, to make time for it and talk about it.

It’s an investment in time and effort. It will always be worth it.